Agriculture and Climate

Written by Dr Estrelita van Rensburg

Greenhouse gases and climate

Maasai and their cattle agriculture

US greenhouse gas emissions

Agriculture’s impact on global greenhouse gas emissions

Natural methane cycle and climate

Traditional livestock agriculture

Climate, soil and carbon sequestration

Climate impact of industrial-scale agriculture

Crops dominate industrial agriculture

Environment impact of industrial agriculture

Industrial agriculture impacts livestock farming

Cows, climate and environment

Introduction – Agriculture and climate

The environmental movement has long been concerned about agriculture and climate. Farming practices and its impact on greenhouse gases emissions frequently come under scrutiny. Cattle raising is increasingly regarded as an ecosystem destroyer because cows belch out methane. What’s more, the thinking is that eating beef is not environmentally responsible. Should we all quit eating meat and embrace this simplistic view? Fact is that there are fewer cattle on the land in the US today than a century ago. In addition, less beef and animal fat are now consumed because of a change in dietary choices, following the dietary guidelines introduced in the 1980s. A more responsible question is how agriculture as a whole is contributing to climate change and greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, what is agriculture's impact compare to that of industry?

Greenhouse gases and climate

Gases that trap heat in the atmosphere are called greenhouse gases. This results in heating up our planet. The three main greenhouse gases are:

- carbon dioxide (CO2)

- methane (CH4)

- nitrous oxide (N2O)

The concern is that human activities globally are responsible for their unprecedented rise. Scientists and politicians are trying to work out the best ways of curtailing emissions – a process, not surprisingly, fraught with difficulty. It is often easy to cast blame on something or someone to suit various agendas including the interests of big business. Agriculture and climate change are complicated topics. It requires us to look deeper into history and, additionally, the impact of farming on our environment.

Maasai and their cattle agriculture

The semi-nomadic Maasai tribe of Kenya offers us a glimpse into the lifestyle of our pre-agricultural ancestors (around 10,000 years ago). Their way of life survived into modern times, showing us how farming cattle meet all of their basic needs: Food, clothing, and shelter. In the 1960s, scientists from the Vanderbilt University studying the tribe were amazed to find that their daily diet comprised meat and a few litres of milk (sometimes mixed with cow’s blood). They considered fruits and vegetables fit only to be eaten by cows! In spite of following an animal protein and mostly saturated fat diet, they were slender of build, their blood pressure was low, and neither did they suffer from chronic diseases such as cancer or diabetes. The animal-based diet provided them with all the nutrients they needed, without the burden of any of the modern lifestyle diseases.1 Compelling information to consider before we decide to blame cows for global warning and dump eating meat. Just how much of the global gas emissions can be blamed on agriculture?

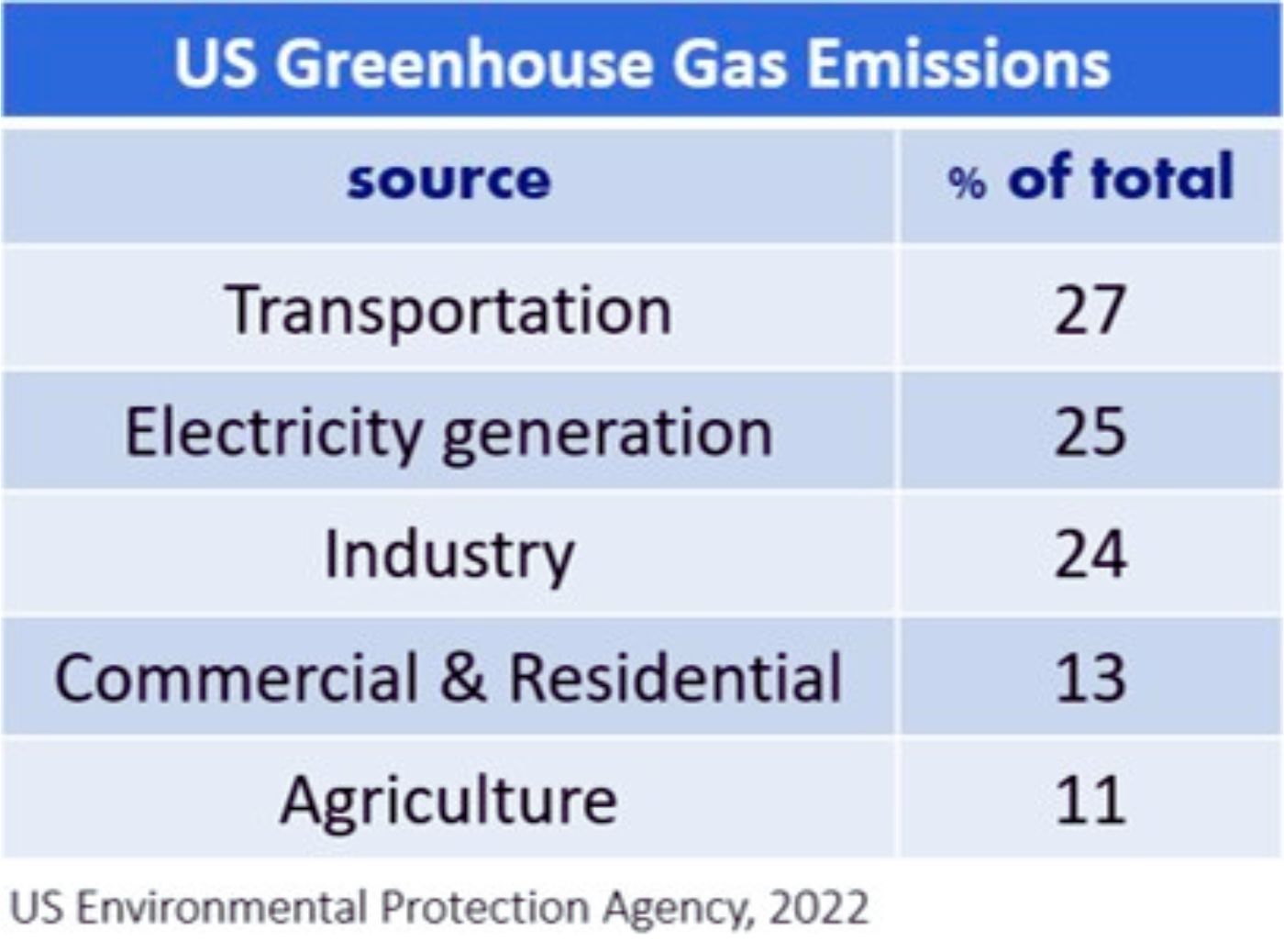

US greenhouse gas emissions

The US Environmental Protection Agency track and report on greenhouse gas emissions. Surprisingly, their 2022 US data shows that, of all the industry sectors, agriculture is the lowest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions at eleven percent. All the others make up the rest (89%). Obviously, blaming cows for the state of affairs is ludicrous, since further analysis shows that livestock agriculture contributes less than crop-based agriculture of total farming emissions.2

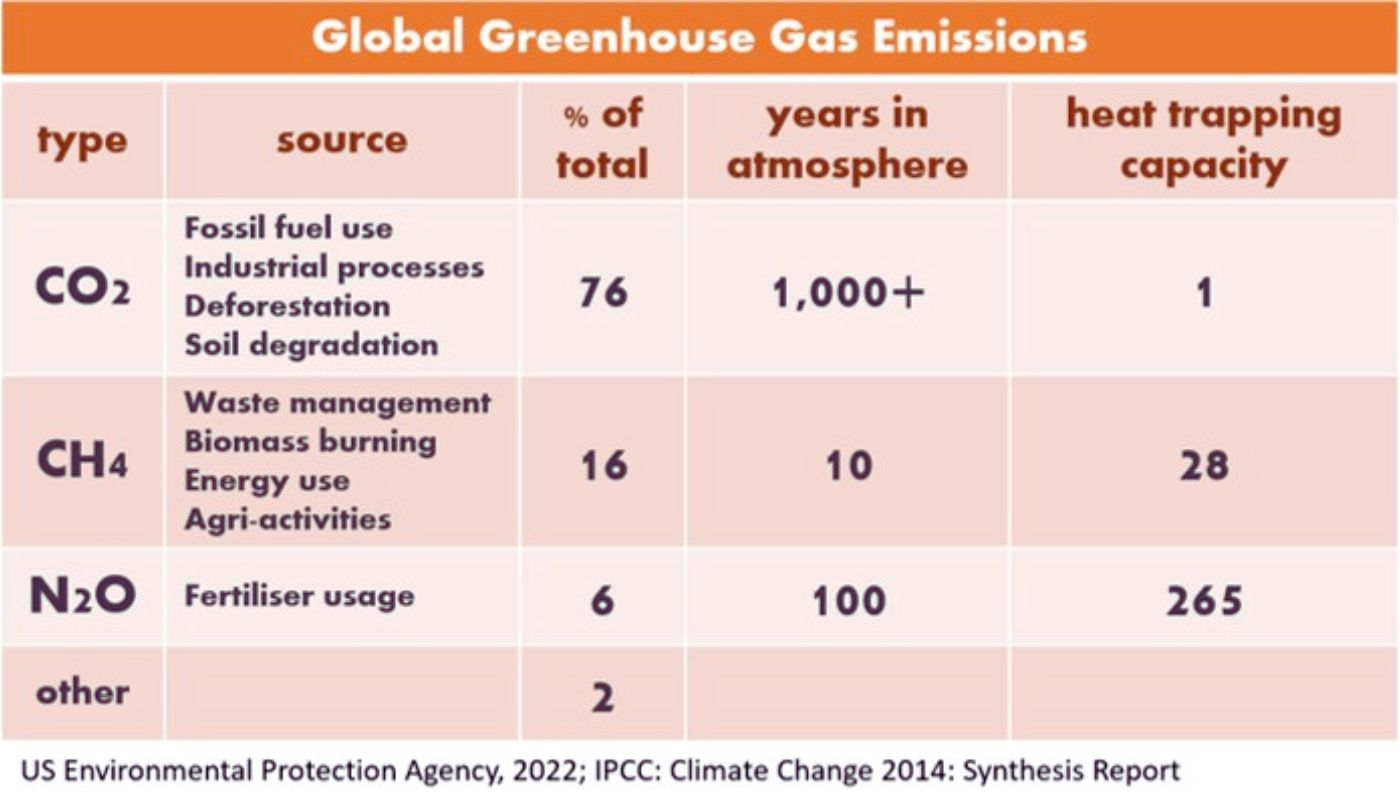

Agriculture’s impact on global greenhouse gas emissions

When looking at specific greenhouse gas emissions from a global perspective, carbon dioxide (CO2) is clearly the largest overall contributor at 76%. Carbon dioxide is also the gas that remains longest in the atmosphere. Methane (CH4) is the second highest contributor at 16%. However, it has the shortest atmospheric time lasting only about a decade in the atmosphere. Nitrous oxide (N2O) at six percent is the smallest contributor to gas emissions, but its heat trapping capacity massively outstrips that of the others. It is 265 times that of carbon dioxide and nearly ten times that of methane. Most nitrous oxide emissions result from the manufacture of man-made fertilizers, which are predominantly used in agriculture crop-farming. With regard to methane, the oil and gas industry is the biggest contributor to emissions, followed by natural wetlands, landfills and rice paddies. These sources dwarf the amount that cows (ruminants) make, which is estimated at four to five percent of the total.3  The data highlights that the most effective way to reduce global emissions is to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, especially fossil fuel consumption. Fossil fuels are also used in agriculture, especially in industrial-scale farming operations, with soil degradation and its climate impact intimately linked to that.

The data highlights that the most effective way to reduce global emissions is to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, especially fossil fuel consumption. Fossil fuels are also used in agriculture, especially in industrial-scale farming operations, with soil degradation and its climate impact intimately linked to that.

Natural methane cycle and climate

To understand how ruminants (cows, sheep, goats and deer) generate methane, we need to understand their digestive systems, which are different from other herbivores. Their stomachs have four separate compartments instead of one, which allows them to digest grass or vegetation without completely chewing it first. Instead, they partially chew vegetation, after which gut microorganisms in the first section (rumen) of the stomach, break down the rest. These microorganisms digest cellulose and complex starches in the vegetation, something that we humans can’t do. Methane is produced as grass and other vegetation ferments in the rumen, which is then expelled by the cow, mainly through belching. Once in the air, methane is converted into water vapour and carbon dioxide in about a decade’s time. These are taken up by plants and converted to carbohydrates via photosynthesis, thus completing the natural cycle. In summary, these animals eat non-human edible vegetation and upcycle it into meat and dairy products. These products are then used by us as sources of essential protein and fat. This process has been around for millions of years.

Traditional livestock agriculture

Ruminants and other herbivores are not only sources of protein and fat for humans but, through their natural grazing activities, they form an integral part in environmental carbon sequestration and soil building. This natural process utilizes two greenhouse gases - carbon dioxide and methane – which are released into the atmosphere by the grazing animals through breathing and belching. As mentioned previously, methane breaks down into carbon dioxide and water over time, both of which are recycled. Plants directly absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to produce carbon molecules via photosynthesis. The carbon is then transported through to their root systems and into the soil (carbon sinking or sequestration). The by-product of photosynthesis is oxygen. This is released into the air to be breathed in by the animals, completing the natural cycle above ground.

Climate, soil and carbon sequestration

In the soil, a fine network of fungal filaments (microrrhizal fungi) picks up carbon and uses it to produce soil glue, called glomalin. Glomalin helps in forming soil clumps and soil aggregates in conjunction with soil bacteria and nutrients. Animal manure itself is another important carbon source that seeps into the soil to participate in the soil building process. Soil nutrients are transported back into plant root systems and so complete the efficient bio-eco exchange system.4

Grazing cows help with carbon sequestration and soil building

Once this ecosystem is operational, the formation of topsoil can be breathtakingly rapid, contrary to what most people are led to believe. Carbon is a key driver of soil health and critical for its water-holding capacity. Traditional farming practices contribute very little carbon dioxide and methane emissions, because animals are kept outdoors which doesn't require a lot of machinery usage. The climate impact is therefore, unsurprisingly, very little. This is called regenerative farming, and you DO need a cow to do that. In the words of Professor David Montgomery, ‘Life makes soil. Soil makes more life.’5

Climate impact of industrial-scale agriculture

The way we treat our soil and our land is fundamental to the health and survival of civilization and our planet. Modern-day industrialised agriculture is impacting natural ecosystems on an unprecedented global scale. The nature of farming changed from agriculture diversity, crop rotation with mixed husbandry of plants and animals to large mechanised farms, with single animal or crop species specialisation.

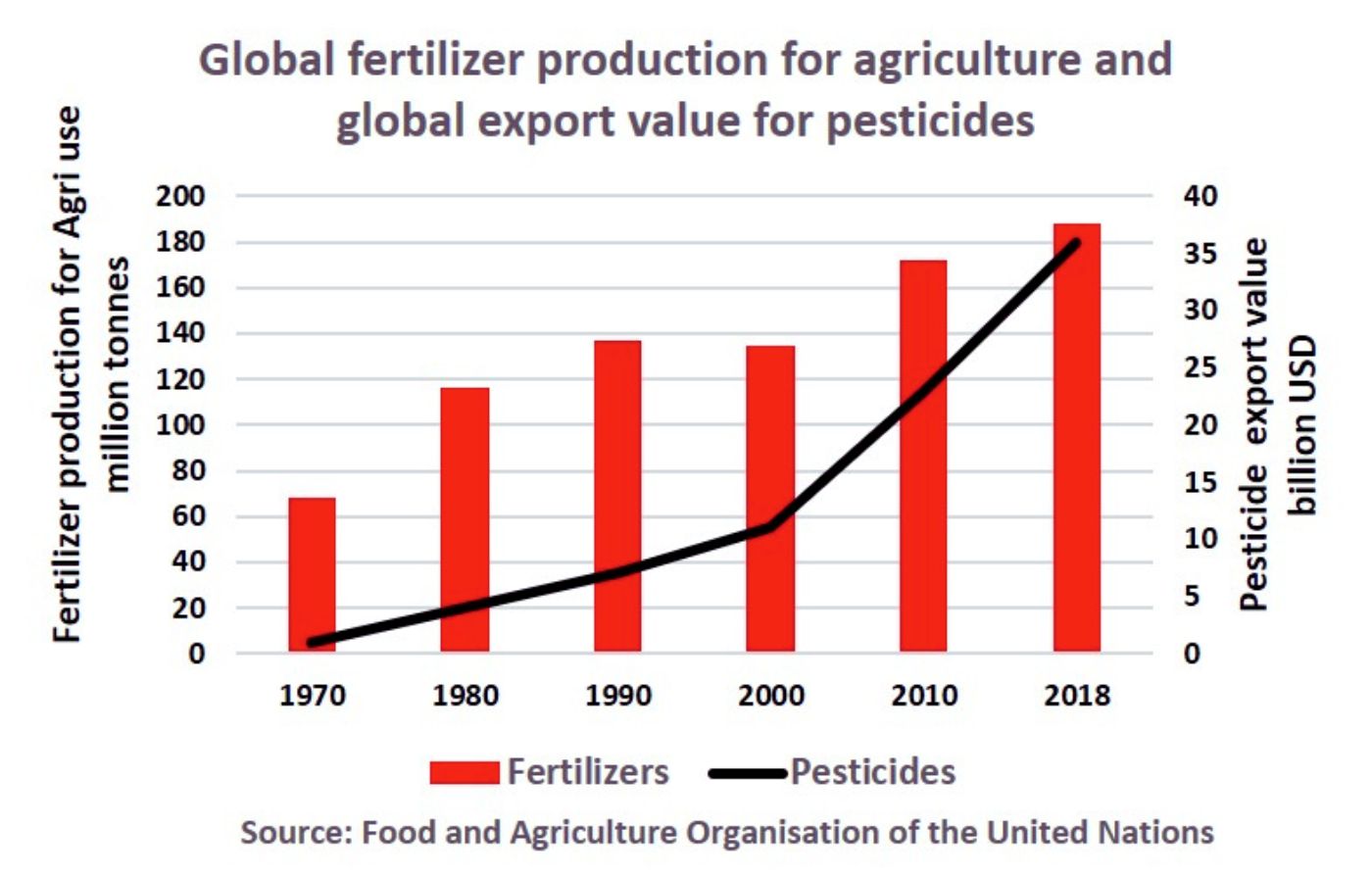

This process kicked off when munitions plants of the World War Two era were converted into manufacturing agricultural chemicals - fertilisers and pesticides. Their production and revenue generation massively increased over the last fifty years (see graph below). Fertilisers, the most important source of nitrous oxide, have a warming potential far exceeding that of any other greenhouse gas.  The utilisation of fertilisers and pesticides dramatically increased the yield of crops when planted as monocultures on farmland. Crop yields definitely increased, but the downside of this farming technique is the destruction of soil. These chemicals destroy the healthy soil composition described before. Additionally, the fine microrrhizal network is mechanically destroyed by tilling/ploughing. The result is an overall reduction in soil organic material, its carbon sink as well as its water-holding capacities. In short, the soil has been changed into dirt. This leads to soil erosion on a massive scale. Crops now require more and more water as dirt can no longer retain water efficiently.6

The utilisation of fertilisers and pesticides dramatically increased the yield of crops when planted as monocultures on farmland. Crop yields definitely increased, but the downside of this farming technique is the destruction of soil. These chemicals destroy the healthy soil composition described before. Additionally, the fine microrrhizal network is mechanically destroyed by tilling/ploughing. The result is an overall reduction in soil organic material, its carbon sink as well as its water-holding capacities. In short, the soil has been changed into dirt. This leads to soil erosion on a massive scale. Crops now require more and more water as dirt can no longer retain water efficiently.6

Industrial agriculture and government subsidies

This model of mega-big farms and farming machinery requires a lot of oil and gas products to run on, with corresponding climate impact. It is an expensive operation to maintain - and in the US richly supported by government subsidies. These big farms became giant food producers, not only driving their own local small farmers and communities out of business, but also flooding overseas markets with cheap grain. It therefore threatens the survival of distant local farmers too. Poorer countries are in no position to compete with giant grain business cartels. Looking at it in another way, modern industrial agricultural methods are running on fossil fuels, with an estimated half a gallon of oil used for every bushel of corn produced.7

Crops dominate industrial agriculture

On a global environmental scale, the production area utilised for the three top crops species (soybeans, wheat and maize/corn), is roughly four percent of the earth’s landmass. There is an incentive for big business crop farmers globally to increase their land acreage, even cutting down Amazonian rain forests to maximise their crop yields. These mega farms now produce huge surpluses of crops, much more than humans can consume. The surpluses are used as cheap food for animal production on an industrial scale and the rest is poured into producing non-edible building materials, called bio composites. This material is used for example to make furniture, flooring, carpets, footwear and biodiesel fuel for diesel engines.8

Environment impact of industrial agriculture

The environmental impact is staggering:9

- decimated the natural habitat of millions of insects, birds and small mammals

- responsible for the decline of pollinators

- extra water requirements for millions of acres of crop fields create dying rivers and sinking water tables

- destroys wetlands and marine life e.g., the chemical fall-off in the Mississippi and Gulf of Mexico, creates a marine dead zone

- millions of prairie herbivores disappeared since the mid-nineteenth century (bison, elk, white-tailed deer, mule deer etc.)

- estimated 100,000 vulnerable species become extinct in tropical forests yearly

- world’s soil erosion now exceeds new soil production by as much as twenty-three billion tons per year

Industrial agriculture impacts livestock farming

With the advent of industrialised crop farming, the concept of ‘zero grazing’ for animals became acceptable. Giant factories called ‘Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations’, or CAFOs, were first established in the US and now found in many countries. Here animals are crowded together in factory farms often standing in their own manure, eating corn. Definitely not their native food, which is grass and other vegetation. They are subsisting on something they were not designed for, which makes them sick. Further, animal waste is collected in manure lagoons, a major source of water and river pollution. The close proximity and permanent herding of the animals expose them to stress and disease, which is controlled by robustly using antibiotics and other medications. The philosophy is to bulk the animals up as quickly as possible, no matter what it takes. Then, slaughter them young, before chronic illness results in visible illness or death.9

Cows, climate and environment

In conclusion, our concern should be the environmental and climate impact of industrial agricultural policies and practices. It overproduces crops. What’s more, this results in cheap food, overeating, waste and pollution. Additionally, it removes the ruminants (cows) from their natural habitat (pasture grazing) and feeds them food that is unnatural, which makes them sick. Not to mention that it removes cows from their natural ecosystem where they contribute to carbon sequestration and soil building. Industrial agriculture helps destroy, not only the environment, but our sense of how to live with other species, big and small. We need to figure out how regenerative farming practices can help us eat within our own bioregion. As Nicolette Hahn Niman says: ‘It is not the cow but the how’. 10 Because of industrial farming practices, global rates of sugar and grain consumption have skyrocketed, leading to global epidemics of various types of chronic illness. If you are interested to learn how to cut out grain and all its negative health effects from your diet, we can help. Dietary change remains the most important part of a healthy lifestyle.

Agriculture and Climate References

- Teicholz N. The Big Fat Surprise. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2014.

- Rodgers D, Wolf R. Sacred Cow. BenBella Books, Dallas, 2020.

- Buxton, J. The Great Plant-Based Con. London: Piatkus, Little Brown Book Group; 2022.

- Comis, Don. Glomalin: Hiding Place for a Third of the World’s Stored Soil Carbon. Agricultural Research Magazine, United States Department of Agriculture Research Service; 2002.4-7.

- Montgomery DR. Growing a Revolution: Bringing our soil back to life. WW Norton & Company, New York. 24753577; PMCID: PMC4035951

- Brown G. Dirt to Soil: One Family’s Journey into Regenerative Agriculture, Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018.

- Pollan, M. The Omnivore’s Dilemma. Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 2011.

- Soybean meal info centre: https://www.soymeal.org/soy-meal-articles/world-soybean-production/; North Carolina Soybean Producers Association, https://ncsoy.org/media-resources/uses-of-soybeans/

- Keith L, The Vegetarian Myth. Flashpoint Press, California, 2009.

- Hahn Niman, N. Defending Beef, the case for sustainable meat production, Chelsea Green Publishing, 2014.